“Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son and shall name him Immanuel.” —Isaiah ben Amoz, 734 BCE (Isa. 7:14)

For nearly twenty centuries, Christians have drawn upon Isaiah’s Immanuel oracle as a prophetic connection in support of the doctrine of Christ’s divinity. Indeed, the Gospel of Matthew references this ancient prophecy in his account of the birth of Jesus:

“All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet: ‘Look, the virgin shall become pregnant and give birth to a son, and they shall name him Immanuel,’ which means, ‘God is with us’” Mt. 1:22-23 (NRSV).

Following this tradition, every year during Christmas season, Christian churches gather together to sing, pray, and reflect upon Jesus as Immanuel. However, in order to better engage with this ancient text and to avoid common misconceptions, it would be helpful for us to explore its original context and learn more about its interpretive history.

Historical Background of the Events of Isaiah 7

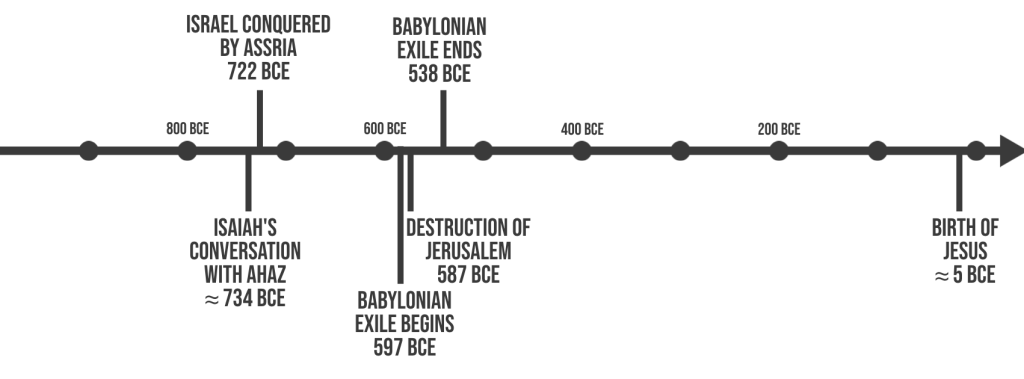

The occasion for this famous encounter between Isaiah son of Amoz with King Ahaz of Judah is at the beginning of the Syro-Ephraimite War (likely 734 BCE). The Assyrian Empire, under Tiglath-Pileser III, is expanding westward, seeming to impose a serious threat to the nations of Syria, Israel, and Judah. Therefore, Rezin, the king of Syria, and Pekah, the king of Israel form a military alliance to withstand any potential Assyrian advance on the region. Seeking to bolster their strength, the joint forces of Israel and Syria plan to besiege Jerusalem and attempt to dethrone Ahaz, installing a puppet king to ensure Judah’s participation in the coalition.[1]

It is immediately before this siege that the conversation depicted in Isaiah 7 between the prophet and the king occurs. Ahaz has been exploring the possibility of reaching out to Assyria to protect Judah from its neighbors to the north in return for paying tribute. Isaiah prophetically challenges Ahaz to resist this urge and to instead put his trust in YHWH, using a small child as a prophetic oracle to communicate the Lord’s impending deliverance. However, as Hyun Chul Paul Kim states, in the end “King Ahaz could not make a leap of faith relying on the prophecy of a little child but instead resorted to submitting to the grown-up Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III.”[2]

Overview of Isaiah 7:1-9

The passage begins with a brief reference to the siege of Jerusalem and Ahaz’s fearful reaction (vv. 1-2). The Lord instructs Isaiah to take his son and meet Ahaz “at the end of the conduit of the upper pool” (v. 3), where Ahaz is likely inspecting the city’s water supply in preparation for the siege.

Isaiah’s prophetic message to Ahaz begins with the exhortation, “Do not fear” (v. 4). Ahaz is assured that the threat from Rezin and Pekah will come to nothing, because they are mere men who are no match for YHWH (vv. 4-9a). However, this promise is conditioned upon Ahaz putting his trust in YHWH rather than in an alliance with Assyria.

Unfortunately, Ahaz will eventually choose the pragmatic option of seeking Assyria’s help. This policy was problematic not simply because of its idolatrous nature, but also because of the resulting burden it would inevitably extend to the ordinary people of Judah. As a result of its alliance with Assyria, Judah would now pay tribute to the empire, which would result in a substantial increase in taxation. While this move would save his political power, it would result in economic hardship for the rest of the population.

The Immanuel Prophecy: Isaiah 7:10-17

Through Isaiah, the Lord now invites Ahaz to ask for a sign, an invitation that is unprecedented in the Bible. Ahaz refuses to ask for a sign, pretending to take the pious approach. In verse 13, Isaiah responds by giving voice to YHWH’s frustration (“Is it too little for you to weary mortals that you weary my God also?”). It seems as though Ahaz’s rejection of a sign betrays his predisposition for an alliance with Assyria.

In the narrative connected to this passage (2 Kings 16), Ahaz’s eventual plea to Tiglath-Pileser III begins with the statement, “I am your servant and your son” (v. 7, emphasis mine). Here, Kim sees a possible source of YHWH’s frustration: “In an intertextual reversal of Psalm 2, where YHWH declares to the Davidic king, ‘you are my son’ (Ps 2:7), Ahaz now renounces this sonship and becomes Assyria’s slave and son.”[3]

Therefore, given Ahaz’s refusal, the Lord gives him a sign: “Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son and shall name him Immanuel” (v. 14b). The Hebrew word for young woman, is ‘almā, which, according to John J. Collins, “can, but does not necessarily, refer to a virgin.”[4] Walter Brueggemann notes that the word simply refers to “a woman of marriageable age.”[5]

There seems to be no suggestion whatsoever that this verse is speaking of a miraculous conception. Among scholars, there are many theories floating around pertaining to the identity of this young woman. I am inclined to agree with the prevailing assumption that whoever she is, she is most likely closely associated with Ahaz, perhaps his wife or a woman in his harem.[6] Regardless, she must be an identifiable figure in order for the sign to have any meaning to Ahaz. The son shall be named Immanuel, meaning “God is with us,” which for Ahaz is meant to serve as a summons to faith, trusting that the Lord will protect and defend Judah.

In vv. 15-16, Isaiah declares, “He shall eat curds and honey by the time he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good. For before the child knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land before whose two kings you are in dread will be deserted.” In other words, the oracle seems to indicate that within a very short time following the child’s birth, the threat will be removed, Judah will live in peace and prosperity, and its northern neighbors will have serious problems of their own.

Finally, verse 17 declares, “The Lord will bring on you and on your people and on your ancestral house such days as have not come since the day that Ephraim departed from Judah—the king of Assyria.” In its immediate context, YHWH turns His attention away from Ahaz and issues a declaration of judgment directly towards Syria and Israel (Ephraim). Indeed, the Assyrians will completely decimate these regions within a short period of time. However, it seems there also might be something else going on. Could this verse possibly be a double-edged sword, addressing multiple audiences living in different time periods?

The Immanuel Prophecy for the Exilic Community

In light of Ahaz’s ultimate refusal to trust in YHWH, verse 17 could also be seen as an intentional harbinger of what will come much later for the nation of Judah at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar in the early 6th Century when Jerusalem is destroyed and many Jews are exiled to Babylon.

The scholarly consensus is that book of Isaiah is an anthology of prophecies and narratives that originated from at least three different sources who lived over a span of at least 200 years. In the ensuing generations, scribes edited and assembled these works into what we now know as the Book of Isaiah.

For reasons I won’t enumerate here, it seems likely that the composers and redactors of this particular passage were shaping this story (set during a much earlier time) in order to speak freshly into the experience of the exilic community following the catastrophe of 587 BCE, challenging them to live in fidelity to YHWH, the true Lord of history.

Immanuel in Christian Interpretation

At some point between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE, the Hebrew text of Isaiah 7 would be translated into Greek and become part of what we now call the “Septuagint” (the Greek translation of the Hebrew canon). The Hebrew word, ‘almā, translated “young woman” in verse 14, becomes parthenos in Greek, commonly translated “virgin.” It is this Greek version of Isaiah 7:14 that will later be cited in Matthew 1:23 in connection to the virgin birth of Christ.

Interestingly, it’s been demonstrated that at the time of its translation, parthenos “did not necessarily refer exclusively to a virgin (though of course it often included that meaning when appropriate), but that it developed to have that sense in a narrower way in the immediately pre-Christian decades.”[7] Thus, linguistic development paved the way for new theological development.

It must be acknowledged that this interpretive innovation on the part of Christians was certainly not anchored to the original intent of Isaiah’s prophecy as found in the text. However, as demonstrated above, the capacity for the prophecy to morph and speak freshly and legitimately into new contexts is embedded into the history and origin of the biblical passage itself. Therefore, as Wegner asserts, Isaiah 7:14 “forms a ‘prophetic pattern’ which Matthew picks up…and fills it with more meaning by applying it to Jesus.”[8]

Concluding Reflections

For Christian interpreters of the Bible, I would like to offer a few thoughts. First, it is necessary that we adopt a humble and open posture in our task of interpreting texts like these. For many centuries, Isaiah 7 has been a battleground between Jewish and Christian interpreters. However, when one learns about the context and history of this beautiful passage, it should be apparent that there is no need to stake an exclusive claim for one interpretation over another. Indeed, the original formation of this text itself is a creative, Spirit-inspired prophetic word for a contemporary audience far removed from the events depicted (much like the musical Hamilton or the 2012 film Lincoln).

Secondly, years ago in my “Hermeneutics” class in Bible College our curriculum instructed us to always use the “historical-critical” method of bible interpretation. The historical-critical method begins with the premise that the meaning of any passage is always located within the author’s intent. Therefore, it stresses the value of using tools to uncover the historical, cultural, and linguistic contexts when engaging in Bible study.

No doubt, embracing the role of context and identifying the author’s intent is always essential in the process of interpretation. However, the assumption that the text’s meaning is always governed by the author’s intent is not only false, but problematic (as this case study hopefully demonstrates). If Christians stubbornly hold to this assumption, we are sawing off the very plank we stand on.

The original authors and redactors of the Book of Isaiah had absolutely no idea that this passage from Isaiah 7 would later spark an entirely new connection that would have nothing to do with King Ahaz or the exilic community. The early Christian community’s association of the Immanuel prophecy with the virgin birth of Christ was a theological innovation aided by new translation and linguistic development that occurred long after the events depicted in Isaiah 7 or the text’s composition.

While the historical-critical method is an invaluable approach to discerning what a passage means in its original setting, it must be recognized that elucidating “meaning” from a text is not a lab science, but an ongoing Spirit-inspired process that often leads in unanticipated directions. This isn’t to say that “meaning” is up-for-grabs for anyone to twist as one likes. Interpretation always belongs within the broader Christian community (guided by the illumination of the Spirit).

However, over and over again, the Bible itself authorizes the creative, Spirit-inspired repurposing of prophetic texts to speak freshly into new contexts. Brueggemann calls this the “generative” capacity of prophecy. Once we embrace this idea, we can not only stand firm on the historical Christian connection of Immanuel with the virgin birth of Christ, but we can also keep our eyes open, looking for new ways in which we are indeed being invited to trust in God and uniquely experience God with us in our own contexts and experiences.

[1] These events are recounted in detail in 2 Kings 16ff and 2 Chron. 28:5ff.

[2] Hyun Chul Paul Kim, Reading Isaiah: A Literary and Theological Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2016), 8.

[3] Kim, Reading Isaiah, 60.

[4] John J. Collins, A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, 3rd ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 218.

[5] Walter Brueggemann, Isaiah 1-39 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998), 70.

[6] For a detailed discussion regarding the woman’s identity, see H. G. M. Williamson, Isaiah 6-12 (New York, NY: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2018), 155-160.

[7] H. G. M. Williamson, Isaiah 6-12 (New York, NY: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2018), 155-160.

[8] Paul Wegner, Isaiah: An Introduction and Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2021), 96-97.