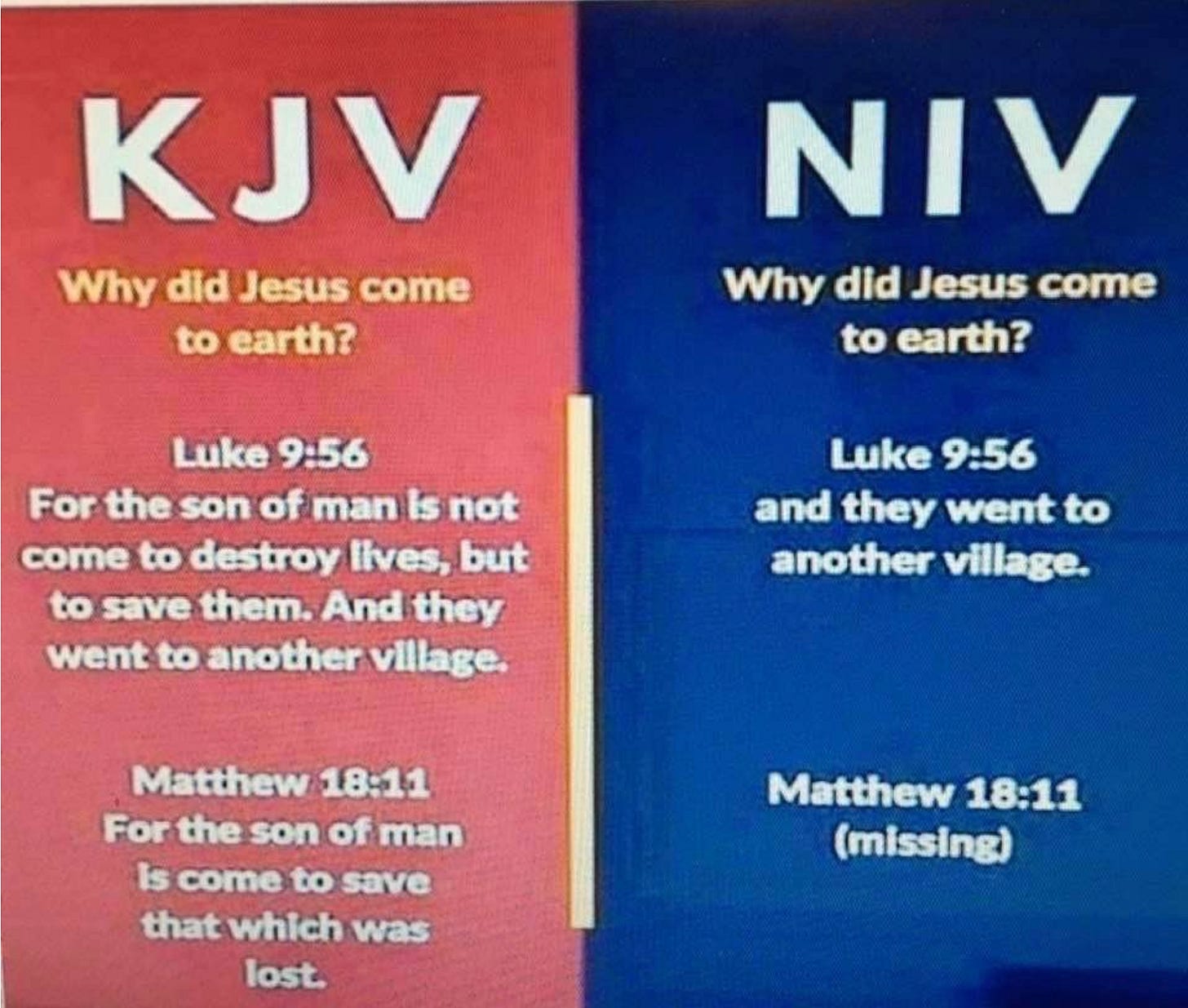

From time to time I come across images shared on social media like the one posted below. I see posts like this one fairly often. I also regularly read and hear comments from Christians who express concerns and questions about Bible translations. Over the years, I have encountered much confusion and misinformation regarding this topic. So I thought a quick primer on Bible translations would make for an interesting article.

“WHY IS THIS VERSE OMITTED IN MY BIBLE?”

First, we do not have any of the original documents of any of the biblical books. But over time, people made copies of the original documents of Scripture. Many copies. And copies were made of those copies. And copies were also made of those copies (and on and on it goes). We currently possess over 5,800 ancient Greek manuscripts. If you include early translations (Latin, Syriac, Coptic, etc.), the number rises to over 20,000.

Before the invention of the printing press, all copies were handwritten. Therefore, occasionally scribes made inadvertent mistakes (spelling errors, forgotten words, missed punctuation, etc.). Sometimes scribes would intentionally adjust a certain verse or section in order to make it more intelligible. And every so often, a scribe might even change the wording to make it more theologically “correct.” Therefore, not every manuscript looks exactly the same.

However, because of the wealth of manuscripts in our possession, textual critics can often determine which readings are earlier and which are later, and in many cases can trace the development of certain textual traditions. Therefore, through the comparison of these manuscripts, these scholars have been able to gain a pretty solid consensus on the text of the original documents.

Which brings me to the image I posted above. Why does the NIV omit some of the wording of Luke 9:56 and totally exclude Matthew 18:11 (by the way, these are just two of many similar examples)? (Sidenote: The NIV is actually one of many modern translations that omit these sections).

The KJV was originally translated in 1611 from the best manuscripts that were available at the time. However, in recent decades (and centuries), many earlier and more reliable ancient manuscripts have been discovered. Through the process of textual comparison, it has been demonstrated that in cases like these, the text that the KJV includes (that the NIV omits) was almost certainly not in the original manuscripts.

There is no sinister agenda here. This especially becomes clear when we realize that there is another version of this saying of Jesus elsewhere that the NIV does include:

“For the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost” (Luke 19:10, NIV)

Why omit this saying in one reference and not the other? Because the issue is not about censoring the Bible. It’s about being as faithful as possible to the actual, original text (something that every Christian should be interested in, right? …Right?).

“IS THERE SUCH A THING AS A WORD-FOR-WORD TRANSLATION?”

There are hundreds of English translations of the Bible. Bible translation is unavoidable. Unless every Christian wants to learn the original languages of the Bible (Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic), we need skilled translators. And translation is not an exact science.

Occasionally I hear people say, “I just want a word-for-word translation of the Bible.”

No, you don’t. For one thing, sentence construction in ancient Greek and Hebrew is completely different from that of modern English. For example, in Matthew 17:18 we find the story of Jesus healing a boy of demonic possession. If we were to translate it directly word-for-word, it would read something like this:

“And rebuked it the Jesus and came out from him the demon and was healed the boy from the hour that.”

This approach would obviously make the Bible unreadable.

But it gets much more complicated than just sentence structure. The ancient languages of the Bible contain tons of words that do not have exact matches in modern English. The opposite is also true. There are plenty of examples in which the English language contains words for specific concepts that do not have an ancient equivalent.

So anyone who claims to use a “literal, word-for-word” translation of the Bible is mistaken and uninformed. It doesn’t exist. Every translation involves some measure of risk, approximation, and concession.

BASIC APPROACHES TO BIBLE TRANSLATION

Translation involves “reproducing the meaning of a text that is in one language as fully as possible in another language” (from Distorting Scripture? by Mark Strauss). There are two basic approaches to accomplishing this.

The formal approach seeks to stay as close as possible to the structure and wording of the original language. As I’ve shown above, this would not be helpful (or even possible) if it were taken to the extreme. Therefore, there is some degree of compromise for the sake of readability (just like with any translation).

The upside with more formal translations is that they stay reasonably faithful to the form and wording of the original language, preserving shades of meaning that might otherwise be lost. The downside is that these translations can sometimes be difficult for the average person to understand.

Some of the best-known examples of more formal translations would be the KJV, NKJV, ASV, RSV, and NRSV.

The functional approach is focused more on expressing the meaning of the original text into today’s language. Some of the more contemporary translations (like the NLT and CEV) are well-known for this approach. The upside of the functional approach is that these translations are much more readable and understandable for the average person. The downside is that if it veers too far from the form of the original language, it can lose shades of meaning.

There are also other translations that try to find some measure of balance between the two approaches (the NIV, NEB, and ESV are prominent examples).

“WHAT SHOULD I LOOK FOR IN A BIBLE TRANSLATION?”

I have always enjoyed using a variety myself. When it comes to praying through the Psalms, I love the poetic, Shakespearean English of the KJV/NKJV. When it comes to study and preaching, I mostly lean on the NRSV.

But when it comes to daily reading, I bounce around a bit. I’ve learned that every translation has its strengths and weaknesses.

But here would be my general advice to the average churchgoer.

First, find a translation you can understand. If you can’t understand anything, what’s the point? For people who are somewhat new to Christianity, I tend to recommend the New Living Translation (NLT) as a great starting point.

I used to advise people to rely more on translations that were formulated by a committee rather than by just one person. There is a common assumption that there is an inherent weakness when the translation work is being done by one person. As the argument goes, when the work of translation is undertaken by a committee of respected scholars, there is a natural system of checks and balances that helps prevent one’s own bias or personal convictions from being sneaked into the text. On the other hand, when one is doing the work alone, the text is much more vulnerable to distortion.

However, I have since come to understand that committees can also be biased and slow to adopt fresh thinking. While a committee structure does create internal accountability, it does not eliminate bias; it simply redistributes it. Committees are composed of individuals who often share similar academic training, theological commitments, and institutional affiliations. In some cases, the very process that guards against eccentric interpretation can also produce a kind of intellectual inertia. When consensus is required for progress, the safest or most traditional rendering may be favored over a potentially more accurate but less familiar one.

In the end, every translation reflects careful scholarship, difficult decisions, and a sincere effort to bridge ancient words and modern ears. That reality shouldn’t scare us—it should humble us and make us grateful. Instead of fueling suspicion, let it fuel confidence: we have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to manuscripts, scholarship, and faithful translations. So pick up a Bible you can understand, read it deeply, compare it thoughtfully, and let it shape you. The goal is to know Christ, and the Bible’s task it to reveal him to you.

(Note: I posted a version of this article on my website several years ago. I’ve revised and adapted it to include updated data and to better reflect my current perspective.)